How can the precautionary principle be more effectively applied in biodiversity conservation?

Abstract

The precautionary principle is Principle 15 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. It states that “Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation”. Despite Australia being a leader in adopting the precautionary principle, there is still a lack of clarity in regard to its application in environmental decision-making. A precautionary approach is not being taken in regard to the assessment of development impacts on biodiversity, with the environmental impact assessment (EIA) of individual projects not addressing the cumulative effects of multiple projects or the policies that influence individual projects. If the precautionary principle is to be effectively applied in biodiversity conservation then an alternative to the EIA approach is needed. Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is one way of addressing the deficiencies of EIA. SEA can give effect to the precautionary principle through the adoption of a landscape ecology approach, where priority conservation zones are identified in which development needs to discharge a ‘no harm’ threshold. This approach has already been successfully implemented in the Lockyer Valley region of South East Queensland. However, while the introduction of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 facilitated such approaches, the Australian Government has not effectively advanced them.

Introduction

The precautionary principle is Principle 15 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (UN General Assembly, 1992). It states that:

In order to protect the environment, the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities. Where there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.

The origin of the precautionary principle is thought to be the German concept Vorsorgeprinzip, which is the principle of foresight and planning (Godden and Peel, 2010). It has become a high-profile principle of international environmental law, and is widely endorsed in Australian environmental policy (Godden and Peel, 2010). In December 1992, the Council of Australian Governments (COAG) endorsed the National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development, with the precautionary principle as one of its guiding principles (Ecologically Sustainable Development Steering Committee, 1992). Also in 1992, the precautionary principle was endorsed as a principle of environmental policy in the Intergovernmental Agreement on the Environment (IGAE) between the Commonwealth, states, territories and the Australian Local Government Association (COAG, 1992). In the time since, the precautionary principle has been widely incorporated into Commonwealth and state legislation. This has been mostly through the inclusion of the principle as an objective, but in some cases it also appears in legislative provisions.

Despite Australia being a leader in adopting the precautionary principle, there is still a lack of clarity in regard to its application in environmental decision-making (Godden and Peel, 2010, Peel, 2009). In response, a large body of literature has emerged with a wide range of recommendations about how the principle can be better applied (Godden and Peel, 2010). This essay explores the potential for a key recommendation from this literature, which is for the greater use of strategic environmental assessment (SEA), to address issues raised by one of Australia’s best-known precautionary principle legal cases, Leatch v Director-General of National Parks and Wildlife (NSWLEC, 1993).

Discussion

The Leatch case

The Leatch v Director-General of National Parks and Wildlife Service case (the Leatch case) (NSWLEC, 1993) relates to a 1993 appeal against the granting of a licence to Shoalhaven City Council to take or kill endangered fauna associated with a road proposal at North Nowra on the NSW south coast. Council had sought to construct a bridge and associated road link across Bomaderry Creek gorge to relieve traffic congestion. The case judgement (NSWLEC, 1993) summarises the issues raised in regard to the precautionary principle.

In late 1991, Shoalhaven City Council had applied to itself as consent authority for development approval to construct the road link. The application was supported by a Review of Environmental Factors (REF). The REF had identified diverse vegetation communities in Bomaderry Creek gorge and adjacent areas, as well as a number of rare plant species including Eucalyptus langleyi, Dampeira rodwayana and Zieria baeuerlenii. The small shrub Zieria baeuerlenii is found nowhere else in the world, and is listed as an endangered species under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 and NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995 (SEWPaC, 2013a). The REF also reported that diverse fauna communities would be expected in the area of the gorge, but advised that fauna impacts were likely to be negligible even though the gorge area was thought to host the most significant fauna habitat within the Nowra town area.

In July 1992, the Director-General of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service provided Shoalhaven City Council with the specifications for a Fauna Impact Statement (FIS). A full fauna survey was required, and was to include assessment of endangered species including the Yellow-bellied Glider, Diamond Python and Tiger Quoll. Consultants were engaged by council to prepare the FIS, and later in 1992 council resolved to approve the road development application, subject to consent conditions and the FIS recommendations being satisfactory.

In February 1993, Shoalhaven City Council applied to the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service for a licence to take or kill endangered fauna, and included the FIS with its application. The service advertised the licence application and FIS, and received several public submissions including at least two that drew attention to the precautionary principle. The FIS was criticised as being inadequate, and the concerns raised included that the Giant Burrowing Frog, which had been listed as a threatened species subsequent to the FIS, may be present. The service assessed the report as deficient, and requested additional information. Council consultants provided a further report which stated that the area was not considered quality habitat for the Giant Burrowing Frog, and because of this the proposed road link would not impact the species. This was despite the council consultants hearing the calls of the frog while surveying for other species, an observation that had not been mentioned in the FIS. Despite service staff still having reservations, the Director-General granted the licence.

In July 1993, Mrs Leatch, who had made a public submission on the licence application and FIS, appealed the decision through application to the NSW Land and Environment Court. The hearing was held in November 1993 before Justice Paul Stein. As it had been raised in the public submissions and by Mrs Leatch’s solicitor, Justice Stein considered the relevance and appropriateness of the precautionary principle to the appeal. He expressed the view that “the precautionary principle is a statement of common sense and has already been applied by decision-makers in appropriate circumstances” (NSWLEC, 1993). He concluded that there was a “dearth of knowledge” in regard to the Giant Burrowing Frog, and that “application of the precautionary principle appears to me to be most apt in a situation of a scarcity of scientific knowledge of species population, habitat and impacts” (NSWLEC, 1993). In consideration of this and potential impacts on both the Giant Burrowing Frog and Yellow-bellied Glider, Justice Stein upheld the appeal and refused the licence. In doing so he stated that alternatives should be further explored, consistent with the expression of the precautionary principle in the Intergovernmental Agreement on the Environment (IGAE).

Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA)

It had not been clear to the key decision-makers in the Leatch case, Shoalhaven City Council, that the precautionary principle applied to assessment of the environmental impacts of the proposed Bomaderry Creek gorge road link, or how it could or should be applied to such an assessment. Dovers (2006) advises that the environmental impact assessment (EIA) of individual projects, such as occurred with the proposed Bomaderry Creek gorge road link, does not address the cumulative effects of multiple projects or the policies that influence individual projects. The Leatch case judgement mentions cumulative impacts from a number of sources on the environment of the Bomaderry Creek gorge area but the EIA for the road link proposal could only address the road link impacts, and as discussed by Justice Stein the road policies that were behind this specific proposal were not considered either (NSWLEC, 1993).

For decision-makers such as Shoalhaven City Council to be able to act differently in future in response to the issues raised by the Leatch case judgement, then clearly an alternative to the EIA approach is needed. Dovers (2006) proposes strategic environmental assessment (SEA) as one way of addressing the single project focus deficiencies of EIA. SEA analyses the environmental effects of policies, plans and programs, and while it has been used extensively internationally, in particular in the European Union, it has had relatively little application in Australia (Dalal-Clayton and Sadler, 2005). Strategic assessments can be carried out under the Commonwealth Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, but so far only a small number have been or are being undertaken (SEWPaC, 2013b).

A landscape ecology approach to SEA

Dovers (2006) advises that SEA does not specifically incorporate the precautionary principle, but could be adapted for this purpose. Submissions to and the final report from the recently completed Senate Inquiry The effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection in Australia propose mechanisms for achieving this in regard to the threatened species issues that were the focus of the Leatch case (The Senate Environment and Communications References Committee, 2013). The Senate Committee recommends a review of the current Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 strategic assessment approach with the aim of enhancing effectiveness, and the greater use of strategic and regional planning for threatened species conservation (The Senate Environment and Communications References Committee, 2013). The committee notes the support for the greater use of strategic assessments and regional environmental planning given by Melbourne Law School Professors Lee Godden and Jacqueline Peel (The Senate Environment and Communications References Committee, 2013). In their submission to the inquiry, Godden and Peel (2012, p.4) suggest that:

Consideration might be given to strategic assessments which adopt a landscape ecology approach and which identify priority conservation zones where the case for development might involve the precautionary principle, such that where there is a risk of irreversible harm this alters the burden of proof to one where the development needs to discharge a ‘no harm’ threshold.

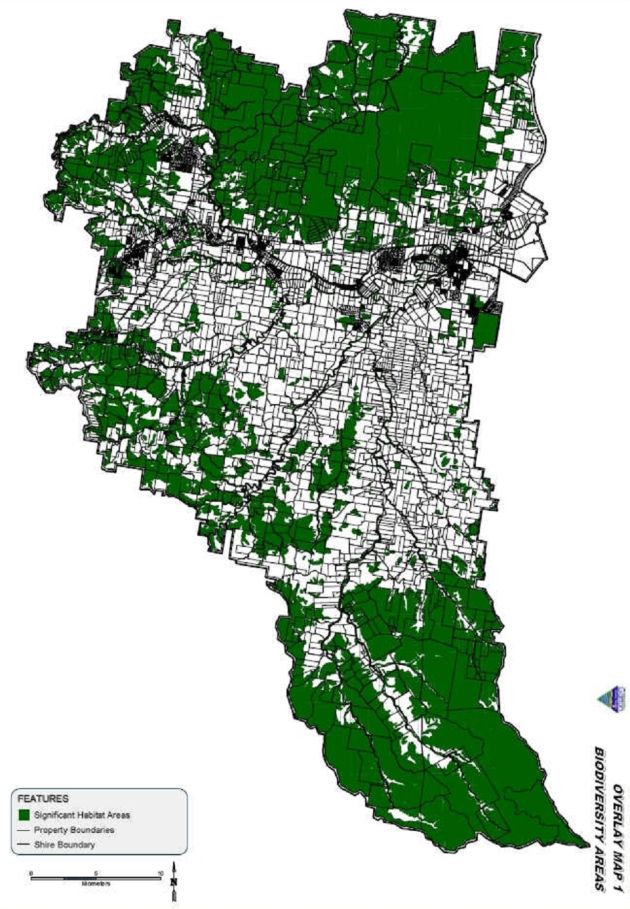

As referenced in the Senate Inquiry Report (The Senate Environment and Communications References Committee, 2013, pp.60,181), an example of such an approach is the Biodiversity Recovery Plan for Gatton and Laidley Shires, South-East Queensland (Boyes, 2004a, Boyes, 2012). This plan covers a defined geographic region, the Lockyer Valley in South East Queensland. Taking a precautionary approach, it addresses the conservation of all threatened species and ecosystems listed under Commonwealth and Queensland legislation, as well as other regionally significant species. Highlighting the extent to which a precautionary approach was taken in the plan, these regionally significant species include species that had been recently removed from the Commonwealth or Queensland threatened species lists, unlisted species where there was concern about decline or potential decline, and species with a restricted or disjunct occurrence in the region. The area comprising the identified habitat of all of the significant species and the significant ecosystems is included in a ‘Biodiversity Overlay’ conservation zone in the Gatton Shire Planning Scheme (Gatton Shire Council, 2007). Within this zone, a Biodiversity Code and Biodiversity Policy applies (Gatton Shire Council, 2007), requiring development applicants to demonstrate proof of ‘no harm’ as proposed by Godden and Peel (2012, p.4). Uncertainty in regard to the presence or absence of threatened species and lack of knowledge about their habitat requirements was an issue raised by the Leatch case (NSWLEC, 1993). To address this uncertainty, the recovery plan requires that a precautionary approach be taken to the potential presence or absence of species and their utilisation of habitat:

The significant species listed for each Regional Ecosystem are the species that are known to utilise that Regional Ecosystem habitat within the Gatton and Laidley Shire area. These species may or may not be present in patches of that Regional Ecosystem on a given property at a given time. However, the presence or absence of a particular species at any given time does not mean that it is not using the Regional Ecosystem habitat at other times. For example, a particular bird species may utilise several scattered patches of the same Regional Ecosystem habitat. It may be found in only one patch at a given time, but need all of the patches for its survival. In another example, a particular plant species may appear to be absent, but is actually present as seeds that will germinate after the next fire. (Boyes, 2004b, p.4).

The Biodiversity Recovery Plan for Gatton and Laidley Shires, South-East Queensland also addresses another key recommendation of Godden and Peel (2010) in regard to improving the implementation of the precautionary principle, which is the incorporation of non-scientific inputs. The preparation of the Biodiversity Recovery Plan was overseen by a recovery team chaired by the Lockyer Watershed Management Association (LWMA) Inc. Lockyer Landcare Group, and members of the team included representatives from Landcare and Catchment Management Groups, the Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service (QPWS), Gatton and Laidley Shire Councils, The University of Queensland Gatton Campus, the University of Southern Queensland, the Toowoomba Bird Observers Group and Greening Australia (Boyes, 2004a). The recovery team facilitated a high-level of up-front community involvement in the development of the recovery plan. This contrasts with the very narrow opportunity for public input into Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) processes, as highlighted by the Leatch case where the only opportunity for input was after the Fauna Impact Statement (FIS) had already been prepared (NSWLEC, 1993).

Progress of the landscape ecology approach

In a keynote presentation to the 1998 World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) South-East Queensland Rainforest Recovery Conference, Alex Rankin, then Director of the Threatened Species and Communities Section of Environment Australia, foreshadowed the regional and multi-species recovery planning approaches that would be made possible when new legislation was introduced, this legislation being the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Rankin, 1999). She stated that:

…the new Bill offers a broader range of opportunities for the content and form of recovery plans, including covering multiple-species or regional ecosystems in the one plan and adoption of plans that are not drafted as recovery plans but which contain the necessary elements of a recovery plan. (Rankin, 1999, p.75).

However, in the hearings for the 2013 Senate Inquiry The effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection in Australia, Deborah Callister, Assistant Secretary, Wildlife Branch of Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC) stated that:

We are looking at things such as moving from species-by-species approaches to recovery planning to more regional approaches or multi-species plans where we think that that is appropriate. (Commonwealth of Australia, 2013, p.69).

The closeness of the two statements shows that the Australian Government has not effectively advanced landscape ecology approaches in the 15 years that separates the statements. Many of the 2013 Senate Inquiry submissions and hearing participants expressed frustration at the lack of progress in regard to strategic assessments and regional biodiversity planning, and in response the Senate Committee has recommended that SEWPaC streamline processes and achieve outcomes within strict, monitored timelines (The Senate Environment and Communications References Committee, 2013).

Conclusion

The Leatch case revealed that the environmental impact assessment (EIA) of individual projects does not address the cumulative effects of multiple projects or the policies that influence individual projects. If the precautionary principle is to be effectively applied in threatened species decision-making then clearly an alternative to the EIA approach is needed. Strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is one way of addressing the single project focus deficiencies of EIA. SEA can give effect to the precautionary principle through the adoption of a landscape ecology approach, where priority conservation zones are identified in which development needs to discharge a ‘no harm’ threshold. This approach has already been successfully implemented in the Lockyer Valley region of South East Queensland. However, while the introduction of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 facilitated such approaches, the Australian Government has not effectively advanced them. It is hoped that the spotlight shined on this inaction by the recent Senate Inquiry The effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection in Australia leads to positive change.

References

BOYES, B. 2004a. Biodiversity Recovery Plan for Gatton and Laidley Shires, South-East Queensland, 2003-2008, Version 2, 5 March 2004. Forest Hill: Lockyer Catchment Association (LCA) Inc. Available: https://bruceboyes.info/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Gatton_Laidley_Biodiversity_Recovery_Plan_Version_2.pdf [Accessed 25 January 2014].

BOYES, B. 2004b. Regional Ecosystem Management Principles for Gatton and Laidley Shires, South-East Queensland. Appendix A to the Biodiversity Recovery Plan for Gatton and Laidley Shires, South-East Queensland 2003-2008. Version 2, 5 March 2004. Forest Hill: Lockyer Catchment Association (LCA) Inc. Available: https://bruceboyes.info/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/Recovery_Plan_Appendix_A_Version_2.pdf [Accessed 25 January 2014].

BOYES, B. 2012. Regional Biodiversity Recovery Planning Submission. Available: https://senate.aph.gov.au/submissions/comittees/viewdocument.aspx?id=1bb5415f-32e3-4c39-b967-99a673274b68 [Accessed 25 January 2014].

COAG. 1992. Intergovernmental Agreement on the Environment. Council of Australian Governments (COAG). Available: http://www.environment.gov.au/node/13008 [Accessed 25 January 2014].

COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA. 2013. Official Committee Hansard, Senate Environment and Communications References Committee, The effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection in Australia, Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Retaining Federal Approval Powers) 2012. Friday 15 February 2013. Available: http://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:%22committees/commsen/a21d3fde-f61d-4158-982c-12af7bbc1c26/0000%22 [Accessed 25 January 2014].

DALAL-CLAYTON, D. B. & SADLER, B. 2005. Strategic environmental assessment: a sourcebook and reference guide to international experience, London, Earthscan.

DOVERS, S. 2006. Precautionary policy assessment for sustainability. In: FISHER, E., JONES, J. S. & VON SCHOMBERG, R. (eds.) Implementing the Precautionary Principle: Perspectives and Prospects. Edward Elgar Publishing, Incorporated.

ECOLOGICALLY SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT STEERING COMMITTEE. 1992. National Strategy for Ecologically Sustainable Development. Available: http://www.environment.gov.au/about/esd/publications/strategy/index.html [Accessed 25 January 2014].

GATTON SHIRE COUNCIL 2007. Planning Scheme. Gatton, Queensland: Gatton Shire Council.

GODDEN, L. & PEEL, J. 2010. Environmental Law: Scientific, Policy and Regulatory Dimensions, Oxford University Press Australia & New Zealand.

GODDEN, L. & PEEL, J. 2012. Submission to the Inquiry into the Effectiveness of Threatened Species and Ecological Communities’ Protection in Australia, 14 December 2012. Melbourne Law School. Available: https://senate.aph.gov.au/submissions/comittees/viewdocument.aspx?id=ffcb8755-e4f2-41d0-8087-580330c78479 [Accessed 25 January 2014].

NSWLEC. 1993. Director-General of National Parks & Wildlife Service v. Shoalhaven City Council [1993] NSWLEC 191 (23 November 1993). Land and Environment Court of New South Wales (NSWLEC). Available: http://www.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/sinodisp/au/cases/nsw/NSWLEC/1993/191.html?stem=0&synonyms=0&query=leatch [Accessed 25 January 2014].

PEEL, J. 2009. Interpretation and Application of the Precautionary Principle: Australia’s Contribution. Review of European Community & International Environmental Law, 18, 11-25.

RANKIN, A. 1999. A lot can happen in a millennium: the changing role of government in threatened species conservation. In: BOYES, B. R. (ed.) Rainforest Recovery for the New Millennium. Proceedings of the World Wide Fund For Nature 1998 South-East Queensland Rainforest Recovery Conference. Sydney: WWF. Available: https://bruceboyes.info/wp-content/uploads/2010/01/1998_SE_QLD_Rainforest_Conference_Proceedings.pdf [Accessed 25 January 2014].

SEWPAC. 2013a. Zieria baeuerlenii – Bomaderry Zieria, Bomaderry Creek Zieria. Species Profile and Threats Database (SPRAT), Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC). Available: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/publicspecies.pl?taxon_id=56781 [Accessed 25 January 2014].

SEWPAC. 2013b. Strategic assessments. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPaC). Available: http://www.environment.gov.au/topics/environment-protection/environment-assessments/strategic-assessments [Accessed 25 January 2014].

THE SENATE ENVIRONMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS REFERENCES COMMITTEE. 2013. The effectiveness of threatened species and ecological communities’ protection in Australia. Commonwealth of Australia. Available: http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/Senate/Environment_and_Communications/Completed_inquiries/2010-13/threatenedspecies/index [Accessed 25 January 2014].

UN GENERAL ASSEMBLY. 1992. Rio Declaration on Environment and Development. Annex I of Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (Rio de Janeiro, 3-14 June 1992), United Nations General Assembly. Available: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/conf151/aconf15126-1annex1.htm [Accessed 25 January 2014].