Putting Australia’s carbon tax axing into perspective

Australia’s new Coalition government led by Prime Minister Tony Abbott is moving ahead with its election commitment to axe the carbon tax. This action is being described as a huge leap backwards. But is it really such a dramatic change of direction? Let’s explore Australia’s climate change policy history.

20 years of delays and policy flip-flopping

Global political action to address climate change began soon after the United Nations had successfully negotiated the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change came into force in 1994 – 20 years ago – and had the aim of preventing dangerous human interference in the climate system. The Kyoto Protocol, which subsequently operationalised the Convention, was adopted three years later in 1997. However, due to a complex ratification process, the Protocol did not come into force until early 2005, more than ten years after the Convention.

Australia’s commitment in the first Kyoto Protocol commitment period (2008-12) was not to decrease greenhouse gas emissions, but rather to increase them by 8%. However, even though there was no commitment to decrease greenhouse gas emissions, the then Howard Coalition Government refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol. It wasn’t until after the first Rudd Labor Government was elected that Australia ratified Kyoto, with that ratification coming into force in 2008. At that time Kevin Rudd described climate change as the great moral challenge of our generation. However, it wasn’t long before he started to falter on his commitment to address climate change, deferring his emissions trading bill until 2012 in what Tim Flannery described as an abrupt and dramatic policy reversal.

After ousting Kevin Rudd, Julia Gillard stated that there would be no carbon tax under a government that she led, but left the door open to putting a price on carbon. However in a deal for power with the Greens she subsequently reversed her no carbon tax promise, committing to introduce one, and was heavily criticised for this reversal. After Kevin Rudd ousted Julia Gillard he axed the carbon tax, going to the election with a promise to end the fixed price on carbon and move to an emissions trading scheme a year earlier than planned. Tony Abbott went to the election promising to end carbon pricing completely, and instead implement the Coalition’s new Direct Action Plan.

Additionally, while putting a price on carbon is a necessary step in addressing climate change, it alone is not enough. Governments also need to facilitate a shift from investment in fossil fuel infrastructure to investment in sustainable energy. Australia has had a Renewable Energy Target (RET) since 2001, currently requiring that at least 20 per cent of Australia’s electricity comes from renewable sources by 2020. But, while some progress has been made the RET falls well short of what is possible, with a transition to 100% renewable energy within ten years being technically and economically feasible for Australia. There are currently fears that the Abbott Government will remove the RET.

So, 20 years after the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Australia still doesn’t yet have policy in place to effectively address greenhouse gas emissions. With the first Kyoto Protocol commitment period ending in 2012, the international community has been negotiating a second commitment period. The commitment of the Rudd/Gillard Government had been criticised and the new Abbott Government has effectively snubbed the current major international climate change negotiations.

Similar histories of climate change policy failure can also be written for many other countries. New Zealand has refused to commit to a second Kyoto Protocol commitment period at all, and Canada has also abandoned its carbon tax. This abandonment is despite research showing the environmental and economic benefits of a carbon tax shift in Canada’s province of British Columbia. A factor contributing to the climate change policy failures in Australia, New Zealand and Canada has been the extraordinary rise of climate change science denial in Anglo-Saxon countries.

Meanwhile, through the 20 years of delays and policy flip-flopping, the dangerous human interference in the climate system that the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change had aimed to prevent has arrived. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) concluded in 2007 that warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and Australia’s former Climate Commission found there has been a significant rise in extreme weather in the past decade.

The Eastlink campaign

My own personal experiences with climate change policy began in 1995, just one year after the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change came into force. The Queensland and New South Wales Governments had proposed to construct the Eastlink electricity connection between the two states as part of plan for a national electricity grid. After seeing a map that showed the easement route passing through high conservation value areas in the Lockyer Valley where I lived, I joined others in establishing the Lockyer Valley Against Eastlink group. This group joined with the other local groups that formed along the powerline route and the conservation movement to mount a campaign opposing Eastlink. As a member of the executive of the Queensland Conservation Council (QCC) at the time, I established and chaired a Sustainable Energy Working Group of QCC to assist the campaign and facilitate input into Queensland Government energy policy.

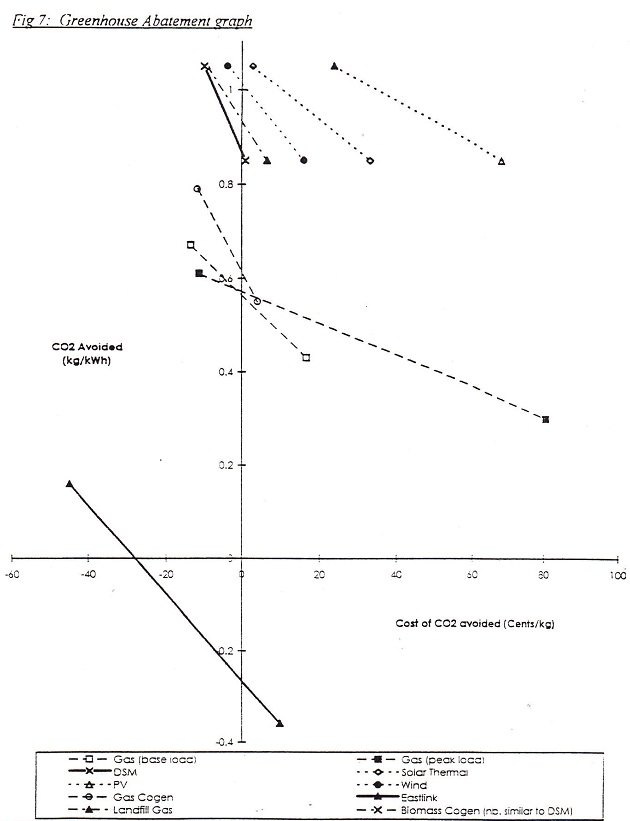

A key aspect of the Eastlink campaign strategy was a Senate Inquiry initiated by the Australian Democrats, with an earlier Senate Inquiry having raised concerns that an electricity grid connection between Queensland and New South Wales could hamper renewable energy development. As well as concerns about the direct impacts of the Eastlink powerline and easement, there were concerns that the grid interconnection would lead to an increase in greenhouse gas emissions by favouring coal-fired electricity over cleaner energy options. A Senate Inquiry submission commissioned by Greenpeace and the Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) confirmed these fears. As shown in Figure 7 of the report, Eastlink was actually the option least likely to result in greenhouse savings. I also prepared a submission assessing the direct environmental impacts of the Eastlink powerline and easement, including a critique of shortcomings of the EIA process.

The Eastlink Senate Inquiry summary report made significant recommendations in regard to greenhouse gas emissions and renewable energy:

Chapter 6 – Electricity Consumption and Greenhouse

The question of impact on greenhouse gas emissions hinges on whether Eastlink will increase the use of coal fired power stations. Because there is almost no data available which relates specifically to Eastlink, the Committee is unable to make a decision as to which is the more likely outcome. However, the Committee notes that the potential does exist for greenhouse gas emissions to increase. The Committee therefore recommends that the Commonwealth Government investigate in detail the likely impact of Eastlink on coal consumption and the implications of any change in that consumption for greenhouse gas emissions having regard to its international obligations.

Chapter 7 – Renewable Alternatives

Throughout the current inquiry, the Committee was impressed by the knowledge and enthusiasm that community groups and individuals hold for alternative renewable forms of electricity generation.

The Senate Standing Committee on Industry, Science and Technology in its 1992 report, Gas & Electricity – Combining Efficiency and Greenhouse, stated that Queensland would be an ideal place to further research on renewables and recommended that the development of a national grid must not preclude the further development of options such as demand management, co-generation and new technologies.

Despite the outcome of the Eastlink interconnection, the Committee reiterates the opinion expressed in the Report on Gas and Electricity that Queensland would be an ideal place for increased research and development of renewable energy options.

The Senate Committee also addressed the concerns in regard to the direct environmental impacts and the EIA process:

Chapter 3 – Environmental Impact

The Committee accepts that there will be some direct environmental impact associated with the construction of this high voltage powerline. The primary impact will be loss of trees through clearing of easement and resultant fragmentation of habitat. Other potential environmental impacts include soil erosion, the introduction of noxious weeds during construction and maintenance activities, the use of herbicides to control vegetation regrowth along easements, the unfavourable visual impact of the line, and impact on special heritage areas.

Of greater concern to the Committee is, however, the actions of the power authorities in determining the preferred corridor, then carrying out the Environmental Impact Statement. While the final impact statement is not due to be completed until mid-1996, it is clear that the power authorities have already chosen a specific route.

The Committee questions the practice of carrying out an environmental impact assessment of a proposal when alternatives have not been included in the detailed Environmental Impact Statement and when siting of the line is clearly going ahead before the Environmental Impact Statement is complete.

What has changed?

So what changed as a result of the 1995 Eastlink Senate Inquiry recommendations? Very little. The Commonwealth did little to further investigate the greenhouse impacts of Eastlink and the Queensland Government little to further explore renewable energy options. All the Queensland Government did was to move the interconnection further inland into far less populated areas. There are also still considerable shortcomings in EIA processes. A successful legal challenge means that the greenhouse impact of burning mined coal must now be addressed in New South Wales EIA processes, but actions to limit this ability can be expected as part of current changes to Commonwealth-State environmental approval processes.

Way back then in 1995, there was a high public awareness of climate change and climate science, and at the time we all assumed that within a few short years the world would have acted to prevent climate change disaster. If someone had come to us in 1995 and suggested that in 2013 we would have the climate change policy situation we have now we would have laughed them out of the room.

The Coalitions’s axing of the carbon tax is a certainly a backwards step, but at no point has Australia had meaningful forward climate change policy progress.

Postcript: Subsequent to the publication of this article, the Parliament of Australia Parliamentary Library produced a Timeline of Australian climate change policy. In introducing the timeline, the authors state that “Climate change is a long-term, global problem. Long-term problems generally require stable but flexible policy implementation over time. However, Australia’s commitment to climate action over the past three decades could be seen as inconsistent and lacking in direction”.